|

|

USAF Presidential helicopter

As the Cold War arms race intensified during the 1950s, the Soviet Union steadily upgraded its strategic bomber and submarine forces. United States strategists began to fear that the Soviets might launch a successful first strike using nuclear weapons. The U. S. government constructed underground command centers to protect the national leadership and allow it to maintain its authority in the event of a nuclear strike. These bunkers were located in rural areas and U. S. strategic planners conducted several exercises to test how quickly national leaders could travel from downtown Washington to these command posts outside the city.

During one civil defense drill, President Dwight D. Eisenhower rode in his personal limousine while cabinet members flew in a helicopter and arrived at the bunker far sooner than the president. This sobering outcome sparked the search for a suitable helicopter to whisk the Chief Executive to safety.

President Eisenhower's chief pilot, Air Force Colonel William G. Draper, had spent most of the President 's term searching for small aircraft, including helicopters, capable of carrying the chief executive comfortably and safely between Washington and the small airport near his farm at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Until 1955, the Secret Service had refused to allow the President to fly in any aircraft equipped with less than four engines. After Secret Service flight rules eased, a single-engine helicopter appeared very convenient for presidential transport because it could operate from the White House lawn. Draper studied, then rejected, the large Sikorsky cargo helicopters because of the noise they produced and their questionable safety record. He discovered that many Bell Model 47s, while reliable, could comfortably carry a pilot, the President, and a Secret Service agent. Early in 1957, Draper decided that the Bell H-13J Ranger was ideal for the chief executive's needs. The United States Air Force purchased two UH-13Js in March 1957 for use as the first Presidential helicopters. These new aircraft were nearly identical to the standard production Ranger configured as a commercial executive transport. Bell only added two new features to the presidential version; all-metal rotor blades to increase the helicopter's useful load, and special tinting to the huge Plexiglas nose bubble to reduce glare and heat.

Air Force spokesmen played down the national defense role when "The New York Times" announced the purchase of the President's new helicopters on February 20, 1957. The Times article mentioned only that these aircraft would shorten Eisenhower's trips from the White House to the Military Air Transport terminal at National airport, across the Potomac River. Leapfrogging road traffic, the Chief Executive could quickly dismount his Bell 47 and board one of the larger airplanes dedicated to his use, a Lockheed Super Constellation named "Columbine III," or one of the two, twin-engine Aero Commanders used for shorter trips. Col. Draper also chose Eisenhower's personal helicopter pilot, Air Force Maj. Joseph E. Barrett. He selected Barrett because of his extensive record as a combat pilot. Barrett flew Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses in World War II, and he was awarded the Silver Star during the Korean War for a helicopter rescue flight he undertook 70 miles behind enemy lines.

A Pennsylvania newspaper created an uproar when it reported that Eisenhower, an avid golfer, "will become so fond of this means of transportation he'll begin using the Rangers for trips to … Burning Tree Country Club." The Air Force quickly countered by admitting that the President would fly in the helicopter during a major civil defense exercise called "Operation Alert." This admission quieted criticism of the helicopters as an extravagant and useless perk. "Operation Alert" began on July 12, 1957, and by mid-afternoon on July 13, President Eisenhower had became the first Chief Executive to fly in a helicopter when he took off from the White House lawn in a Bell UH-13J. Maj. Barrett flew the H-13J bearing serial number 57-2729. He carried President Eisenhower and a Secret Service agent. The President sat in the right rear seat but leaned against a special armrest installed for him on the center seat. He also used a special footrest. The second Ranger, serial number 57-2728, carried the President's personal physician and another Secret Service agent. Both helicopters were based at National Airport, along with the other presidential aircraft.

In September 1957, Eisenhower made an unscheduled return trip from Newport, Rhode Island, and he flew aboard a Marine Sikorsky UH-34D Seahorse helicopter for part of this journey. The passenger cabin inside the Seahorse was more than three times the size of the Bell Ranger compartment and the President immediately recognized the advantages of flying in this much larger helicopter. The Bell could not carry aides or family members and seemed cramped even during short flights. Because the Air Force helicopter mission precluded operating these large helicopters, the Army and the Marine Corps formed detachments to operate the UH-34 helicopters for presidential transport, but relegated the H-13Js to carrying other VIPs. Eisenhower tried to avoid favoring either service by alternating his trips between the Army and Marine Sikorskys. For a time, both services maintained presidential helicopter units but eventually the Marine Corps took over the job exclusively, and to this day, the official Presidential helicopter is designated "Marine One."

The Air Force presidential helicopter mission ended with the Eisenhower presidency. On March 1, 1962, following their assignment as Presidential aircraft, the two UH-13Js were assigned to the 1001st Helicopter Squadron, Bolling Air Force Base across the Anacostia River from Washington. This unit provided VIP transport to cabinet members, defense department officials, and occasionally the Vice President. In 1962, the Air Force added a "U" to the H-13J's designation prefix to denote its utility function. The Air Force retired both of the former Presidential transport UH-13J's in July 1967 and transferred the helicopters to museums the following year. The Smithsonian Institution received 57-2729 and the United States Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio, accepted the other aircraft, serial number 57-2728.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|

1001st Helicopter Squadron

|

|

|

|

Orbie Robertson provides the following information on the 1001st Squadron:

The 1001st had a war time mission calling for airlift of key DOD personnel from the Pentagon to the alternate command post, near Fort Meade. I don't remember the official name for this facility, buried at the bottom of a mountain there. We just called it "R" site. Not far away, on top of this mountain is Camp David, if that will help you place it. We were sworn to secrecy for only 15 years after leaving the assignment. So, no problem revealing this now. This was the principle reason we couldn't get far from Bolling, except for rare occasions. In carrying out this mission, we had crews on alert at the squadron day and night.

Our secondary mission was to provide transportation as needed for high ranking DOD military & civilian, and occasionally Congressmen. For that purpose, we kept the air path between the Pentagon and Andrews pretty well occupied. The squadron had a Bell 47H, which was used pretty exclusively for transporting people like LeMay. Several of the pilots were designated to that mission.

Looking at the last membership list I have, I've found the following names of guys who were with the 1001st at the same time I was:

Don Aamodt, Tony Argo, Marc Barthello, Bob Bunker, Scotty Hancock, Bob Hawes, Baylor Haynes, Ed Quinlan, John Slattery (something of a heli. history buff), Mel Swindells, Dave Vaughn, Charley Wicker, Willie Williams, Herb Zehnder.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DIED AND GONE TO HEAVEN

Those who served with the 1001st Helicopter Squadron at Bolling AFB will probably agree that we did an awful lot of training while awaiting, without eagerness, the time we might have to put into effect our wartime mission. Bolling was my Air Force home from early 1962 ‘til mid-1967. It was a real treat, under these circumstances, just to plan a flight following the Beltway around D. C. clockwise – or counter-clockwise, for a change of scenery. Therefore, when a mission came along taking one out of the traffic pattern, it was like dying and going to heaven. In this vein, I died and went to heaven on 15 October 1964.

At this time, Lyndon Johnson was campaigning for the presidency. For his scheduled visit to Cincinnati on 16 October, Earl May and I were assigned a mission support role. On the appointed day, we picked up a Secret Service agent at the Cincinnati Airport. This gent was armed with an AR-15, and mysteriously seemed totally lacking of a sense of humor. We strapped him into a harness, and he positioned himself at the forward cabin door with his feet hanging outside the helicopter. Naturally, he had radio contact with his supervisor, who advised him of Johnson’s entourage departing the airport. We then took off and flew the left side of the highway, staying about ½ mile ahead of the motorcade. Note: The agent had warned us that Johnson didn’t want our H-21 to be associated with him in the public’s mind. Meanwhile, this Secret Service guy kept a sharp eye on hill and building tops. Of his intentions, I had no doubt. So far, this was a routine mission, the only difference being that we were supporting the Commander-In-Chief - who didn’t want the public to know we were supporting him.

Now, earlier in my career I had experienced a number of in-flight engine failures in the H-21. But these were where the only things one had to contend with were trees, mountains, etc. No big deal! But when we arrived downtown and I had a close-up look at those concrete and steel sky-scrapers, with streets loaded with people, cars, and power poles, I tell you, apprehension took on a life of its own.

No sweat, though! As soon as Johnson entered his hotel of destination, our part was completed. Gratefully, we exited those the city’s yawning maws of destruction by the shortest route possible, and prepared to return to Bolling the next day. And, yes! It was good to die and go to heaven.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

WEBSTER SPRINGS, WEST (BY GUM) VIRGINIA

Earlier, I wrote of a helicopter mission in support of Lyndon Johnson’s campaign for the presidency in 1964. This little tale is a natural follow-on, because it occurred on the return from that mission.

Leaving President Johnson to doing what he did best, Earl May and I departed Cincinnati for Charleston, West Virginia on 17 October 64. From the initial weather briefing, we knew that, though we could reach Charleston with no weather complications, from there on everything became “iffy.” By the time we did reach Charleston, things looked even grimmer. It was clear that by dog-legging northeast to Morgantown, thence to D. C., we would avoid the inclement weather facing us if we continued eastward. At the same time, it would nearly double the enroute time to Bolling. And I, having get-home-itis, thumbed my nose at the weather and proceeded to follow my heart’s desire. One thing: the maneuverability of a helicopter gave me great confidence.

About 20 minutes out of Charleston we came upon a small community named Webster Springs, WV. As we flew eastward, the weather continued to close in, and at this juncture we ran out of altitude and visibility simultaneously. Moments earlier, though, we passed an airport situated on a mountain top just north of Webster Springs. To this, I beat a hasty retreat.

Facing us at this airport was – NOTHING! Nothing, that is, but a good, black-top runway! Not even an outhouse! Should we overnight here, it was going to be a grim, damp, cold, and lonely night. The clouds were now resting on the runway. For the sticklers for detail, let’s call it fog. But, one end of the runway ran right to the edge of a cliff overlooking Webster Springs, 1000 feet below. So, darting off the end of the runway, much like a downhill skier leaving the starting gate, we headed downward.

A couple of passes over the town revealed nothing other than a baseball field suitable for landing. This was it, or nothing. Yet, I was filled with trepidation, not knowing what our reception would be. We landed, but before the rotor blades had stopped turning, kids then adults seemed to materialize out of nothing. But, when a police car showed up, I figured we were in for some tall explaining. Before exiting the aircraft, I gathered the crew at the cockpit, and admonished them concerning good behavior, mentioning something about shotgun territory and possessive fathers.

When, finally, the cabin door was opened we found ourselves greeted by a sea of smiling faces. Kids mobbed us, demanding autographs. One young fellow, lacking writing paper, insisted I autograph his arm. Adults were all atwitter with glee at this unique event in their community. When it became clear we weren’t in trouble of any nature, I suggested Earl go to cockpit to keep the exuberant youngsters out of trouble, as the crew chiefs threw open the aircraft for our own mini-armed forces day. The ear-to-ear grin on the policeman’s face also assured me we had nothing to fear.

Next to arrive by car was the owner of the town’s auto dealership. He ferried me to his office, where I called ARTC to close out our flight plan. At the same time, I called the 1001st to advise them of the situation.

This same person also made certain we were steered to the only hotel in town where one could get a beer. There being a dance at the Elks Lodge that evening, we were all invited as honored guests. Because it was a private club, under the alcohol rules governing that county, this was the only place in town where one could get a mixed drink. At the lodge we were taken in tow by that district’s member of the U. S. House of Representatives. From him we learned that a gift for the blarney was probably useful in running for Congress.

When the next day arrived the sun was shining and birds were chirping, so we had no excuse to delay our departure. Back at the auto dealership, I filed my flight plan, and before that day was history we had returned to Bolling. But, Webster Springs, WV, will always be a fond memory.

|

|

Andrews Squadron Acts Fast to Save Stranded Canoeists.

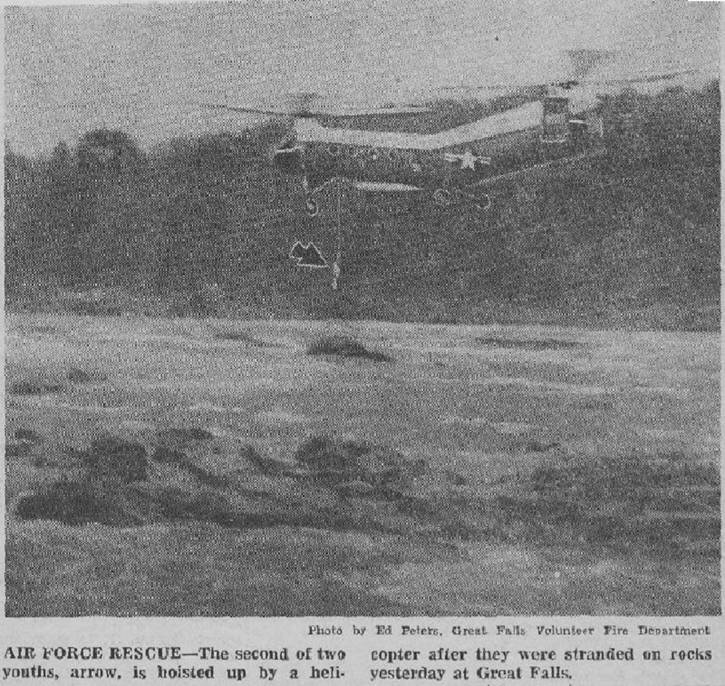

A CH-21 helicopter of Andrews Air Force Base’s 1001st Helicopter Squadron and two youthful canoeists stranded on a rock above a waterfall provided the ingredients for a dramatic rescue Sunday at Great Falls on the Potomac.

Two 16 year olds from Vienna, VA, rented a canoe from a river camp a mile above the falls Sunday afternoon and carried their craft downstream past a dam for launching. Then, as they paddled out into the swift-moving water, their canoe overturned and they were swept toward the falls.

The canoe tumbled over into the rapids below, but before they went over the brink, the boys managed to catch a hold on a large rock in the middle of the river and climb up it to safety.

Dick Steinberg, a member of the Great Falls Rescue Squad, called the Fairfax Count Fire Board after a sightseer reported seeing a canoe swept over the falls. The Board then called Andrews Operations for assistance. The Andrews Operations called Bolling Air Force Base for a rescue helicopter.

Leaving Bolling shortly before 4 pm, Captain Charles Rohr (pilot), Captain Donald Aamodt (co-pilot) and Technical Sergeant Douglas Painter (flight engineer) reached the spot where the boys were stranded within minutes. Sergeant Painter lowered the hoist and brought the uninjured – if not waterlogged- adventurers aboard and then set safely ashore.

Although the CH-21 is not normally used for rescue operations, it is fitted with both a sling and a hoist to give it a rescue capability if the need arise, as it did Sunday.

The 1001st Helicopter Squadron is assigned to Andrews but operates out of Bolling.

1st Helicopter Squadron

The 1001st Helicopter Squadron was redesignated the 1st Helicopter Squadron. Due to congestion in the Bolling AFB area the unit was moved to Andrews AFB in 1969.

|

|

All the personnel of the 1st Helicopter Sq commemorating 25 years & 111,000 accident free flying. Commander at the time Lt.Col. Don Morrissey. DO was Lt. Col. Darwin Edwards. I was assigned as a UH-1N pilot at 1st HS from 1983- 1986. This picture was taken in 1984. The photographer took this photo while standing on a walk way on top of the roof of the huge 1st HS hangar at Andrews AFB. Squadron call sign "MUSSEL". Yes, the fresh water clam. Has to be the worst unit call sign in all of aviation, ever. 1st HS is a unit of the 89th MAW The 1st HS flew the CH-3 version of the H-3 helicopter. Reportedly the light blue and white paint scheme caused the 1st HS helicopters to be very difficult to see in the humid, hazy summers in DC. Mid air collision potential. So, starting in 1984 the 1st HS helicopters were painted dark blue and white top. All VIP helicopters from all the Services in DC have white on the top of the fuselage. Nicknamed "White Tops". (above photo submitted by David Delisio)

|

A VH-1N VIP transport of the 1st Helicopter Squadron takes off from Andrews AFB, Washington, D.C. The aircraft carries a highly attractive scheme of Air Force Blue with a white cabin roof and gold trim. |

|

|

1st HS business card